Stranger Than Fiction

September 2023

The “Human Bomb”: John Thornburg and the Great Chanute Bank Robbery of 1939

by Dean Jobb

A visitor interrupted Joseph F. Balch, a lawyer in Chanute, a city of 10,000 in the southeastern corner of Kansas, as he was conferring with a client. It was midmorning on a March day in 1939, and Balch asked the man to wait in an outer office. As soon as the meeting wrapped up, he motioned to John Thornburg to step inside. They had known each other since elementary school but they were acquaintances, not friends. While Balch had been establishing his law practice, twenty-seven-year-old Thornburg had been bouncing from job to job, picking up work here and there across Kansas and Missouri. The lawyer had no idea why his former schoolmate was in such a hurry to see him.

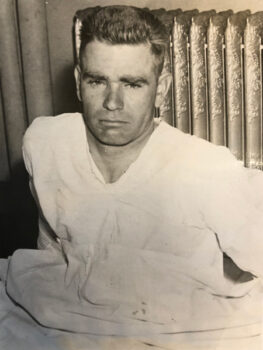

Thornburg, tall, slim, and square-jawed, closed the door behind him. His reddish-brown hair was trimmed in a military-style buzzcut but he was disheveled and needed a shave. He talked incoherently, complaining that his wife had left him a few months earlier, taking their two young children with her.

“You may think I’m crazy,” he said, “but I know exactly what I’m doing.” He held up his left hand, which had been behind his back. Wires were attached to the thumb and forefinger. “If I touch these together, it will complete a circuit and blow the hell out of me, you, and the building.”

Thornburg pulled up the white shirt under his gray coat, revealing three sticks of dynamite, percussion caps, and batteries that were taped to his waist. Then he handed Balch a sack containing a sawed-off, twelve-gauge shotgun and shells and ordered him to load the weapon.

Balch was stunned but did as he was told. “I said to myself, ‘this man is certainly nuts,’” he recalled. “At first I was scared to death and then I figured out I had better be calm.” He had no idea whether the dynamite was real or the contraption worked, and no desire to find out.

“My life isn’t worth a damn,” Thornburg announced, “and nobody else’s is either anymore if you don’t do as I tell you.

“You’re going to help me rob the First National Bank.”

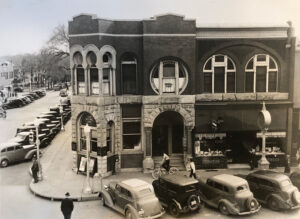

The two men walked side by side as they crossed the street to the bank, which shared a two-story brick building with Conklin’s diner. Sleek sedans and a few outdated Model-Ts were angle-parked and faced the bank’s front door like a fleet of getaway cars pointed in the wrong direction. Balch carried the shotgun, hidden under a newspaper, and no one noticed the bulge under Thornburg’s shirt.

Once inside, Balch approached the bank’s vice-president, B.S. Cofer, and asked if they could meet with him in a conference room. Cofer, who knew Balch’s companion—Thornburg’s aunt was married to one of the bank’s directors—accompanied them to the room. Only then did he realize it was a holdup.

“I’ve thought this all out,” Thornburg told the banker as he showed him the makeshift bomb and the detonation wires. “I want ten thousand dollars.”

Both Balch and Cofer appealed to him to abandon the heist but Thornburg kept threatening to “blow everything to hell.” The bank’s president, James Allen, was called in and confirmed the bank did not have that much money on hand. Thornburg said he would settle for everything in the tills. Cofer went to the tellers’ counter and gathered up stacks of ones, fives, tens, and twenties. Employees assumed a customer was making a large withdrawal or their boss was checking for marked banknotes—loot taken during some recent crime—that might have wound up in the bank’s coffers. None of them suspected they were being robbed.

The bills were wrapped in paper. They added up to $4,860—the equivalent of almost $100,000 today. A Yellow Cab was called and Thornburg, with Balch as a hostage, jumped in. Thornburg told the driver, Ward Lee Scott, he had just robbed the bank and told him to head southwest, toward the Oklahoma state line. He was disappointed with his haul. “I should have robbed the Bank of Commerce while I was at it,” he griped.

Thornburg released Balch and the driver a few miles from the city and roared off. Bank officials had not yet called the police—Thornburg had threatened to blow up the car and his hostages if they did. When Balch phoned from a nearby farmhouse to confirm he and the driver were safe, the hunt began for the brazen robber the newspapers soon christened Chanute’s “Human Bomb.”

The taxi was found a few days later in Fayetteville, Arkansas, about 180 miles southeast of Chanute. The search for Thornburg shifted to the Ozark Mountains and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s G-men joined the hunt. There were a few reports of sightings but no one knew where he was headed or where he might be holed up. The trail went cold.

He was an unlikely outlaw. Thornburg had grown up in Chanute, served as a scoutmaster, taught Sunday school, even delivered a few sermons when the pastor of his church was not available. He had worked in the oil fields, and it was suspected that was where he had learned how to handle dynamite. An explosives expert who operated a local quarry rigged up a bomb similar to the one Balch described and, to his surprise, it worked. “While the explosion likely would have blown Thornburg to bits,” the man reported, “it probably wouldn’t have injured anyone else.”

Thornburg’s split with his wife seemed to have triggered a downward spiral. Not long before the robbery, he was found wandering the streets of Kansas City and suffering from amnesia. He spent time in hospital. “There is undoubtedly something in John Thornburg’s past that he wanted to escape,” a psychiatrist who treated him told a reporter. “He probably planned to take the money far away and start life over.” Whatever he was running from, the crime made him famous. He had robbed the bank, gasped the Chanute Tribune, “in a fantastic manner that rivaled the wildest fiction.

The heist made the pages of the New York Times. When Chanute staged its municipal election shortly after the robbery, Thornburg received a write-in vote for mayor. “One vote is a good poll for the dynamic fellow,” a newspaper columnist joked. “He robbed only one bank.”

Balch, Thornburg’s unwilling accomplice, became a celebrity as well. He posed for a newspaper photograph holding an exploded percussion cap Thornburg had produced in his office before the heist, claiming it proved his body-pack bomb had been tested and would work. Letters poured in from female admirers, law-school classmates, and strangers named Balch who wondered if he might be a distant relative. One of the envelopes was cheekily addressed to “The Balch Bandit Escort Service.” He was invited to speak to a local Kiwanis club on the subject of “Installment Credit” but everyone in attendance wanted to hear about the robbery and his experiences as the hostage of the Human Bomb.

Thornburg, it turned out, was living it up and burning through his windfall. After dumping the taxi in Arkansas, he met a woman in Birmingham, Alabama who robbed him of $400. In Atlanta, he shelled out almost a quarter of his loot on a sporty coupe that he crashed and wrecked. He bought a boat in Florida. He picked up a succession of women as he wandered into Texas and, at one point, he crossed the border into Mexico. He headed to New York in June to tour the grounds of the World’s Fair, which promoted a futuristic “world of tomorrow” and had just opened in the borough of Queens. “I was disappointed in it,” he recalled. “Several of the exhibits were not finished.” He also took in the impressive view from the top of the Empire State Building, the world’s tallest, which had been finished for eight years.

“I wasn’t going any place in particular,” he later explained. “Just roaming, I guess.”

By July, with the money almost gone, he headed home. He hopped on a bus to Nevada, Missouri, a city of 8,000 a little more than an hour’s drive due east of Chanute, and took a room under the name George Griffin. His past caught up to him as he stood on a street corner. A passerby recognized him as his former Sunday school teacher and alerted the police. He was arrested at Bond’s Pool Hall on July 28 after four months on the run. He had two dollars and eighty-four cents in his pockets.

“If I had the words of the greatest of orators, I could not explain why I did it,” Thornburg said after his arrest. “I didn’t need the money.” Balch drove to Missouri for a brief reunion with the man who had made them both famous. Thornburg greeted him with a warm “Hello, Joe” and shook his hand during a visit to his cell. “Apparently he has no hard feelings toward me,” Balch told the press.

At some point a detective asked Thornburg why he had selected the lawyer to accompany him on the robbery. “Oh,” he replied, “I just happened to remember him.” He picked someone who knew the bank’s executives and would take him seriously when he threatened to detonate the bomb. “I had to convince them that I was in earnest.” And if the police were summoned, he reckoned, they would not try to stop him or shoot him for fear of injuring or killing Balch.

A few days later, Thornburg pleaded guilty to robbery and was sentenced to thirty-five years in prison. A defense lawyer claimed the spectacular robbery had been staged to embarrass his family, which had treated him as an “outcast,” and to get the money he needed “to escape from his dull life.” Thornburg expressed no remorse or regret for a crime he attributed to “a peculiar quirk of circumstances.”

After he was sentenced, he dropped a bombshell. The whole scheme had been a hoax. He had emptied the explosive from the sticks of dynamite, he claimed, and refilled them with sawdust. If someone had called his bluff and he had touched the wires together, the percussion caps would have crackled like firecrackers but there would have been no explosion. “I wasn’t counting on having to do that.” One of the FBI agents on the case was sceptical. “Well, his first story was that he used dynamite,” the agent noted. “He has a long time now to make up his mind.”

Thornburg claimed he came up with the plan for the robbery on his own. But six months before his heist, another Kansas man wearing a bomb had been shot and killed by a policeman after robbing a bank in the nearby city of Parsons. And three months after the Chanute robbery a copycat wielding a bomb took about $500 from a bank just fifty miles away in the hamlet of Altamont, Kansas. Thornburg, who was still at large, was ruled out as a suspect and another man was soon arrested as the robber. “Dynamite,” noted the Parsons Sun, “seems to be a new device for bank bandits.”

Thornburg was sent to Leavenworth but by 1943 he had been transferred to a federal prison in Atlanta. He seems to have served no more than a third of his sentence. After his release he moved to California, where he remarried in 1952. His father had been a printer and Thornburg took up the trade, working for several newspapers in Northern California. The Human Bomb’s headline-grabbing crime and spending spree were long forgotten when he died in 1988 at seventy-six.

—-

Esquire magazine selected Dean Jobb’s book Empire of Deception: The Incredible Story of a Master Swindler Who Seduced a City and Captivated the Nation (Algonquin Books), the story of 1920s Chicago con artist Leo Koretz, as one of the 50 best biographies of all time. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. Find him at www.deanjobb.com

Copyright © 2023 Dean Jobb