Stranger Than Fiction

May 2023

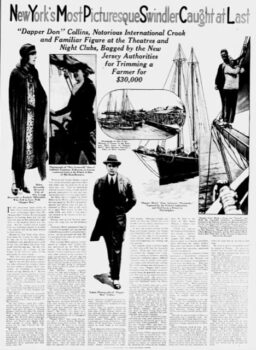

The Jazz Age Crimes of Dapper Don Collins

by Dean Jobb

A tall, smartly dressed man with a cigaret clenched in the corner of his mouth stepped down the gangway of the S.S. Paris, one of the most luxurious of the great liners plying the Atlantic in 1924. The ship’s sumptuous interiors, decorated in a blend of Art Nouveau and Art Deco flourishes, had offered a fitting backdrop for the stylish passenger’s voyage from France.

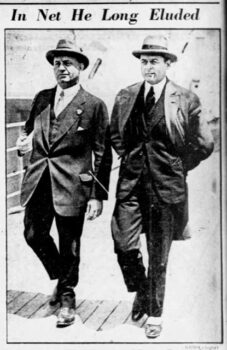

One newspaper reporter who spotted him on a crowded New York pier that June day took stock of his outfit—a tailored suit with topcoat, the brim of a homburg to shade his blue eyes—and declared him “sartorially perfect.” His hands were clasped behind his back as he walked, as if he were a visiting dignitary about to inspect an honor guard.

He was met by a group of men who conveyed him to the dome-capped police headquarters in Lower Manhattan.

“Welcome home,” said the officer on desk duty. “What is your name?”

“Arthur Collins,” he said, smiling, although he could have offered one of more than a dozen other names he liked to use.

“Where do you live?”

“At 101 Center Street. The Hotel Hanley.”

The detectives and reporters surrounding him got the joke. John J. Hanley was warden of the nearby Tombs, New York’s Chateau-style jailhouse. The visitor, a frequent “guest” at that establishment, was “one of the busiest swindlers, confidence men and all-around crooks in the city,” in the assessment of one private detective. The forty-four-year-old specialized in elaborate plots to blackmail wealthy women and had padded his underworld resume with forays into rum-running, drug trafficking, and smuggling illegal aliens into the United States. The Daily News, New York’s crime-obsessed tabloid, once described him as “America’s most wanted criminal.” He may even have gotten away with murder.

Meet “Dapper Don” Collins, one of the boldest, slipperiest, and best-dressed crooks in Jazz Age New York.

* * *

Born in Atlanta in 1880, Collins—his real name was Robert Arthur Tourbillon—started down a path that led many youths to a life of crime: He ran away to join the circus. He performed bicycle stunts and developed a signature act he called the “circle of death,” which involved cycling inside a cage filled with a dozen lions. The daredevil stunt no doubt made swindling, stealing, and smuggling seem like safer professions.

He arrived in New York in 1901 and worked as a model at a Fifth Avenue tailor’s shop, a job that likely fostered his excellent taste in clothes. He was accused of stealing $500 from a saloon in 1907, which first put him on the radar of Manhattan detectives. In 1911, a judge who convicted him of robbing a hotel clerk—earning Collins one of his earliest stints in the Tombs—called him “the cleverest scoundrel in the city.” A prosecution three years later for robbing and assaulting an actress fizzled when the woman refused to testify. He served time in a federal prison in his hometown, Atlanta, for using the mails to defraud, and was back in New York by 1917.

As the Roaring Twenties dawned, the former lion tamer graduated to the big leagues of crime. When a railroad employee absconded with $5,000, Collins tracked him down to a Manhattan apartment, posed as a detective, and agreed not to arrest the fugitive in exchange for relieving him of the loot. He refined the blackmail scheme, recruited a gang, and made a killing by extorting money from wealthy women. Once he had befriended a target—aided by his good looks, charm, and millionaire’s wardrobe—confederates posing as police officers would burst in and accuse him of being a pimp. The shocked woman, desperate to protect her reputation and avoid a scandal, would hand over money, jewels, or furs to bribe the officers and save Collins from being carted off to prison. Women traveling alone on ocean liners became his preferred prey. He was an equal-opportunity crook. “His activities have embraced about all the grades of larceny,” marveled one detective—a real one—who was on his trail. He thought big. He bought a war-surplus navy speedboat in 1922, converted it into a luxury yacht, and posed as a millionaire on a vacation cruise so he could smuggle illegal booze from the Bahamas to New Jersey. No scam, however, was too small. He ducked out of hotels without paying the bills, broke into mailboxes to steal valuables sent by post, and at one point organized a crew that looted nickels and dimes from pay phones. He “could never pass up a score,” he admitted.

Collins always seemed to be one step ahead of the authorities. “The New York detectives,” he boasted, “couldn’t detect a horseshoe in a plate of hash.” When it looked like charges might stick, he hired William Fallon—a slick lawyer with dubious ethics, dubbed “The Great Mouthpiece” of Broadway—to throw up legal flak to stall or derail the prosecution. Fallon was once asked why he defended the notorious ne’er-do-well. “He is a philosopher,” the lawyer explained. “He performs in a gentlemanly manner.”

The gentlemanly crook’s luck soon ran out. Collins was publicly named as a suspect in a couple of high-profile murders. Facing a year behind bars for theft and an attempted murder indictment for shooting a man when a blackmail plot went awry, he fled to Europe. He was in custody in Paris in 1924 for pulling a swindle, and calling himself Arthur Hussey, when two New York detectives, in town to pick up another fugitive, recognized him and arranged for his extradition. Collins insisted on traveling home in style, splurging on a $4,400 stateroom that he paid for out of his own pocket. Fellow passengers took one look at his fashionable attire and assumed Detective Sergeant Joseph Daly, the officer guarding him on the voyage, must be the crook being escorted back to New York. Collins relished the confusion and started referring to Daly as “my secretary.”

* * *

Collins served six months for the theft that led to his extradition from France. Released in early 1925—“more dapper than ever, and a little stouter than before,” the New York Times noted—he was scooped up by federal agents and finally charged with smuggling liquor on his yacht. He was shipped to New Jersey to stand trial and was acquitted, but his troubles multiplied. His well-heeled fiancée, the former wife of a Chicago millionaire, broke off their engagement. He was nabbed for bilking a hotel out of $300, then arrested for possessing a pint of booze. He was the victim of “frameups,” he griped in the press. “I may retire to a farm until things quiet down.”

The closest he got to a farm was when he duped a New Jersey farmer out of $30,000 in a stock swindle. He was arrested and stood trial in Paterson, NJ in the spring of 1929 and tried to work his charm on the eight women on the twelve-member jury. A tearful young blonde—likely enlisted to win the jurors’ sympathy—sat at the back of the courtroom as Collins, turned out in a double-breasted blue suit, took the stand, denied committing fraud, and sparred with the prosecutor.

Why, he was asked, did he refuse to give his address to the police when he was arrested?

“I didn’t want them to rob my apartment.”

“What’s your right name?”

“I never tell.”

The jurors deliberated for two hours and pronounced him guilty. He was sentenced to three years in prison at hard labor.

By the time Collins was released in 1932, the stock market had crashed and the world was in the grip of the Great Depression. It was a tough time for a notorious, easily recognized con man to try to earn a dishonest living. One evening a young tabloid gossip columnist named Ed Sullivan—the future television variety-show czar—spotted him in a nightclub, chatting up a patron who owned a Havana casino. Concerned that Collins was in mid-swindle, Sullivan intervened. “Do you think,” the casino owner protested, “that this chump could take me for anything?”

He pulled his final scam in 1938. The man who had dressed to the nines and courted wealthy divorcées had been reduced to shaking down a poor woman for what he once would have considered a pittance. Posing as an immigration officer, he threatened to deport a New York man unless the man’s wife paid him $300. Convicted of extortion and impersonating a federal officer the following year, he was sentenced to a term of fifteen to thirty years in prison under a state law introduced to crack down on repeat offenders. For Collins, who was fifty-nine, it was tantamount to a life sentence. “The only way I’ll ever come out again,” he predicted, “is feet first.”

A notation on inmate No. 96817’s intake form at Sing Sing Prison summed up his life. It read: “No legitimate employment.” He had a record of thirty-two arrests—in Florida, Wisconsin, and other states as well as in New York—but, remarkably, the immigration scam was only his fourth conviction for a felony.

His fancy wardrobe was gone, replaced with a gray prison uniform. The “international swindler” and “easy money specialist” of so many breathless press accounts had been stripped of his swagger. “I am just an old reprobate,” he confessed to a parole officer.

Collins was transferred to Attica Prison in upstate New York, where the warden regarded him as “a very good prisoner, never in trouble, always clean and well-behaved.” The “Colossus of Rogues,” as one New York newspaperman christened him, died of a heart ailment there in 1950, at age seventy.

——————————-

Esquire magazine selected Dean Jobb’s book Empire of Deception: The Incredible Story of a Master Swindler Who Seduced a City and Captivated the Nation (Algonquin Books), the story of 1920s Chicago con artist Leo Koretz, as one of the fifty best biographies of all time. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. Find him at www.deanjobb.com.

Copyright © 2023 Dean Jobb