Stranger Than Fiction

June 2023

Character Studies

by Dean Jobb

What do controversial FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, English solicitor and convicted wife-murderer Herbert Rowse Armstrong, and a motley crew of New York City cops and lawbreakers have in common? They’re all larger-than-life characters and they’re all the subject of recent books. This month, a round-up of fresh takes on people behind the true-crime headlines.

Armstrong’s story reads like the plot of an episode of Midsomer Murders, the long-running television series filled with grisly crimes committed in the bucolic English countryside. In 1922 the solicitor in the Welsh Borders village of Hay-on-Wye was accused of poisoning his wife and attempting to murder his chief rival for the area’s legal business. And, if the busy local rumor mill was to be believed, he was running a one-man poisoning ring that threatened to claim more victims. The allegations made him an international press sensation, the star of “the greatest poison drama of the century,” as one American newspaper put it. “All England is thrilled by the trial of a modern Borgia.” While Armstrong would not live to see it, his case earned the dubious distinction of filling a volume in the Notable British Trials series, catapulting him into the ranks of the country’s most notorious criminals.

Armstrong’s story reads like the plot of an episode of Midsomer Murders, the long-running television series filled with grisly crimes committed in the bucolic English countryside. In 1922 the solicitor in the Welsh Borders village of Hay-on-Wye was accused of poisoning his wife and attempting to murder his chief rival for the area’s legal business. And, if the busy local rumor mill was to be believed, he was running a one-man poisoning ring that threatened to claim more victims. The allegations made him an international press sensation, the star of “the greatest poison drama of the century,” as one American newspaper put it. “All England is thrilled by the trial of a modern Borgia.” While Armstrong would not live to see it, his case earned the dubious distinction of filling a volume in the Notable British Trials series, catapulting him into the ranks of the country’s most notorious criminals.

A century later, U.K.-based former journalist and veteran true crime writer Stephen Bates tackles this story of crimes real and imagined in The Poisonous Solicitor: The True Story Of A 1920s Murder Mystery (Icon Books). And he revisits the case with a question few seem to have asked before—was Armstrong, a prim, meek-looking former army officer, really a ruthless, cold-blooded, poisoner? It’s territory Bates is well suited to explore. His 2014 book The Poisoner: The Life and Times of Victorian England’s Most Notorious Doctor exhumed another suspected serial poisoner, Dr. William Palmer, who was hanged in 1856 for using strychnine to murder a fellow gambler—and plunder the man’s racetrack winnings—and was suspected of killing other friends and family members.

Armstrong fell from the lofty perch of respected pillar of the community to devious killer in record time. “Scepticism turned to doubt,” Bates writes, “doubt to conjecture, conjecture to suspicion and then suspicion to certainty.” Armstrong’s only competitor in Hay, solicitor Oswald Martin, fell ill after sharing tea and sweets at Armstrong’s home. Members of Martin’s family received a box of arsenic-laced chocolates in the mail. The local doctor who had treated Armstrong’s wife Katharine before her death almost a year earlier became convinced she had been poisoned with arsenic. And Armstrong’s dalliance with a woman soon after his wife died and his purchases of large quantities of arsenic—to use as weedkiller, he insisted—made him the prime suspect. Buying the poison in January, when there were no dandelions to kill, raised eyebrows. The packet of arsenic the police found in his pocket on the day of his arrest sealed his fate.

Bates deftly recreates the investigation and trial as he dissects the web of circumstantial evidence that put a noose around Armstrong’s neck. Since the alleged poisonings occurred at the solicitor’s home in Cusop, on the English side of the border, Scotland Yard took charge of the probe. The tale has the trappings of a mystery novel—a clever sleuth, a hard-nosed prosecutor, a doctor with an overactive imagination, a close-knit community, and plenty of intrigue. Was Armstrong a killer or the victim of rumor and innuendo? Check out this stylish, engaging book and put the evidence to the test.

When New York Times reporter Sam Roberts set out to tell the story of the Big Apple through the lives of its most colorful characters, he settled on thirty-one people who have helped to shape the city’s development over the course of its 400-year history. It says something about the city’s brashness and edginess that so many of them are crooks, cops, victims of crime, or somehow became entangled in the legal system. In The New Yorkers: 31 Remarkable People, 400 Years, and the Untold Biography of the World’s Greatest City (Bloomsbury Publishing) he uses their careers—good and bad—and brushes with the law to put human faces on the city’s past. They are, he explains, “among the most remarkable and noteworthy New Yorkers you’ve never heard of.”

When New York Times reporter Sam Roberts set out to tell the story of the Big Apple through the lives of its most colorful characters, he settled on thirty-one people who have helped to shape the city’s development over the course of its 400-year history. It says something about the city’s brashness and edginess that so many of them are crooks, cops, victims of crime, or somehow became entangled in the legal system. In The New Yorkers: 31 Remarkable People, 400 Years, and the Untold Biography of the World’s Greatest City (Bloomsbury Publishing) he uses their careers—good and bad—and brushes with the law to put human faces on the city’s past. They are, he explains, “among the most remarkable and noteworthy New Yorkers you’ve never heard of.”

John Colman falls into the forgotten category. He was the victim of New York’s first recorded homicide, in 1609, during explorer Henry Hudson’s Dutch-financed voyage to the future site of New Amsterdam. It turns out this long-ago crime remains a whodunit. Was Colman the victim of an attack by Native Americans, as widely believed, or was the unpopular, domineering first mate killed by mutinous crewmen under his command? Almost two centuries later, the city was the scene of a more notorious and equally perplexing murder. In 1799 a young carpenter named Levi Weeks stood trial for killing his rumored fiancée, Elma Sands, after her body was found dumped in a well. The case allows Roberts to introduce such luminaries as Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton, who were the legal “dream team” that defended Weeks—and would square off, a few years later, in a fatal duel. Weeks was acquitted and the “Manhattan Well Mystery” remains one of the city’s oldest cold cases.

Christian Harriot’s crime? In 1819, the Mulberry Street butcher stood trial on a charge of “keeping and permitting to run hogs at large in the city of New York.” It was a test case, aimed at curbing the pigs that had been roaming the city for decades. Impoverished residents depended on them for food or raised them for sale and the animals’ scavenging kept the streets clean for free. Their penchant for uprooting cobblestones, frightening horses, digging up gardens, and attacking people, however, made them a menace that had to be controlled. Harriot was convicted and fined, hastening the end of hog rule.

Jacob Hays’ claim to fame? He was the city’s high constable for the first fifty years of the nineteenth century, a job that evolved from front-line law enforcement to a largely ceremonial post. His story tracks the city’s rapid growth and the rising crime rate that came with it. Schoolteacher Elizabeth Jennings defied segregation rules on public transit in 1854, a century before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus. Charles F. Murphy, who ran the powerful, corrupt, and crooked Tammany Hall political machine for the first two decades of the twentieth century, was notoriously tight lipped, apparently recognizing the value of exercising his constitutional right to remain silent 24/7. “Never write when you can speak; never speak when you can nod; never nod when you can blink,” was his reputed advice to talkative colleagues.

There are many more characters in these pages who will appeal to true crime fans. Roberts, who has been a New York journalist for half a century, is the author of previous books about objects and landmark buildings that illuminate the city’s past. This makes him the perfect guide to its remarkable citizens. He does a fine job of providing the context needed to understand the key roles of these historical characters, while revealing the surprising ways many of their stories are intertwined.

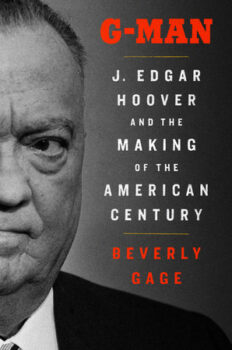

Larger-than-life characters do not come much larger than John Edgar Hoover. The man who ran the Federal Bureau of Investigation for almost fifty years, from 1924 until his death at the helm in 1972, had an outsized impact on American history. His tenure as the country’s chief lawman stretched from the “War on Crime” battles against Depression-era bank robbers and kidnappers to the eve of the Watergate scandal. “He was one of the most influential federal appointees of the twentieth century,” writes Yale University history professor Beverly Gage, “a confidant, counselor, and adversary to eight U.S. presidents.”

Larger-than-life characters do not come much larger than John Edgar Hoover. The man who ran the Federal Bureau of Investigation for almost fifty years, from 1924 until his death at the helm in 1972, had an outsized impact on American history. His tenure as the country’s chief lawman stretched from the “War on Crime” battles against Depression-era bank robbers and kidnappers to the eve of the Watergate scandal. “He was one of the most influential federal appointees of the twentieth century,” writes Yale University history professor Beverly Gage, “a confidant, counselor, and adversary to eight U.S. presidents.”

G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Viking), Gage’s authoritative and immersive biography of the man who built a law-enforcement empire, is as oversized as her subject, clocking in at 732 pages (plus almost 80 pages of endnotes and bibliography). She needed the room to do justice to the formidable and feared Hoover and to document his pivotal role as a Washington powerbroker. She spent a decade poring over more than a million pages of records and unearthed a trove of new material that offers fresh insights into his life, his vendettas against those he perceived as personal or political enemies, and the bureau he created.

It is not a pretty picture. “I do not count myself among Hoover’s admirers,” she admits. “Hoover rose to power and then stayed there, decade after decade, using the tools of the administrative state to create a personal fiefdom unrivaled in U.S. history.” Yet, she adds, he “was more than a one-dimensional tyrant and back-room schemer who strong-armed the rest of the country into submission.” Hoover’s campaigns against left-wing and communist groups and his lesser-known operations to suppress white supremacists, she argues, stemmed from the FBI director’s ingrained conservative vision of American democracy.

“He believed in the power of the federal government to do great things and fight great battles on behalf of the nation’s citizens. He also believed that there were certain groups—communists and racial minorities, above all—who threatened that project.” His odious attacks on Martin Luther King, Jr. and the bugging of the civil rights leader’s hotel rooms are a stain on the FBI’s reputation and his own. Gage makes no apologies for these and other acts that crossed the line, but she weighs them against Hoover’s crime-fighting successes and the bureau’s efforts to stop lynchings in the 1940s and his opposition to the internment of Japanese Americans during World War Two.

Hoover’s contradictions, Gage asserts, are also America’s. “To look at him,” she writes, “is also to look at ourselves, at what Americans valued and fought over during those years, what we tolerated and what we refused to see.” Few characters in American history—least of all an unelected one—have had such a profound impact on their nation and their times.

———

Dean Jobb’s book on a dangerous and devious character, The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer (Algonquin Books), won the inaugural CrimeCon Clue Award for True Crime Book of the Year. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Find him at www.deanjobb.com.

Copyright © 2023 Dean Jobb