Stranger Than Fiction

July 2023

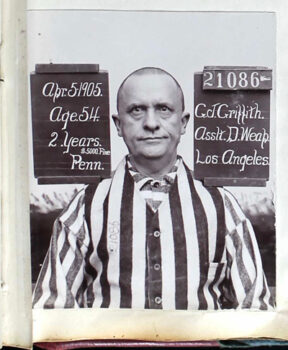

Delusions of Grandeur: The Scandalous Crime of a Los Angeles Millionaire

by Dean Jobb

The couple walked on the beach at Santa Monica that September afternoon in 1903, then stopped at a shop to buy postcards. Once they were back in their suite on the third floor of the oceanside Arcadia Hotel, Tina Griffith began to pack—they were heading home to Los Angeles in the morning. Her husband took his overcoat from a closet and folded it into a trunk before ducking into an adjoining room.

Griffith Jenkins Griffith was one of the richest men in California—at least, he bragged he was to anyone who would listen. The walrus-moustached fifty-three-year-old amassed a fortune by speculating in mining stocks and real estate. In 1896 he donated a vast swath of ranch land and wilderness—five square miles in the rugged hills north of Los Angeles—to the city. He envisioned Griffith Park, as it was named in his honor, as “a place of recreation and rest for the masses, a resort for the rank and file, for the plain people.” A seat on the city’s Board of Park Commissioners ensured he would oversee its development.

Mary Agnes Christina Griffith was thirty-nine. A devout Catholic, she was the daughter of Louis Mesmer, proprietor of the United States Hotel, one of the finest in Los Angeles. She had inherited a valuable plot of downtown land from local businessman André Briswalter, a family friend who died in 1885, making her as rich as her husband, if not richer. A newspaper headline described their marriage in 1887 as the “Union of Two Very Wealthy Los Angeles Families.”

Griffith returned to the room with Tina’s prayer book and handed it to her.

“Get down on your knees,” he said, “and swear to some questions.”

She was startled and did as she was told. As she knelt, she realized he was holding a .38-caliber Smith & Wesson revolver. She implored him to put it away.

“Close your eyes,” he commanded. She whispered a prayer as he reached into a pocket and pulled out a piece of paper. “I am a dead shot,” he reminded her, and began to read his questions.

Did she poison André Briswalter? He had died of blood poisoning brought on by an infection, but Griffith seemed convinced she had been responsible. She assured him she had nothing to do with his death.

Griffith demanded to know if she had ever tried to poison him.

“You know I have not, papa. I have never harmed a hair on your head.”

His third question: Had she ever been unfaithful to him?

“You know I have not,” she pleaded.

He pulled the trigger.

* * *

A day passed before news of the shooting surfaced in the press. Details were sketchy. Tina was in critical condition in hospital. It was rumored her husband had shot her or she had tried to commit suicide. When a reporter for the Los Angeles Evening Express caught up with Griffith, he claimed the shooting was “purely accidental” and his wife’s wounds were minor. No, he said when the question was asked, he had not shot her. “There never has been any trouble between my wife and myself,” he insisted.

Within hours newspapers across the United States had the real story. Griffith had shot his wife in the face at close range. Tina Griffith had sprung to her feet, covered her bleeding face with her hands, and crashed through a screen window to escape. She landed on a porch roof a dozen feet below, breaking a shoulder blade. She managed to open and crawl through a window and into a room on the second floor, where hotel staff came to her rescue.

The bullet struck the outer rim of her eye socket and broke in two. One fragment slashed across her forehead but did not penetrate the skull. The other lodged at the back of her right eye and the eyeball had to be surgically removed. She had been “disfigured for life,” as one news report put it, and was lucky to be alive. If she had not turned her head a split second before the shot was fired, the wound would likely have been fatal.

From her hospital bed, Tina dictated a statement to the district attorney describing what had happened. Griffith, doubling down on his claim the shooting was an accident, told the papers that his wife had dropped the revolver as she was packing and it had gone off. He was arrested, charged with attempted murder, and released on $15,000 bail as he awaited trial.

“The whole social and business world are agog with gossip,” noted the city’s Evening Post-Record. The shooting was “one of the most sensational affairs that has in recent years stirred the upper crust of Los Angeles society.” And one question eclipsed all others: Could a man with so much money and power be convicted and sent to prison?

* * *

Griffith Griffith, born on a farm near Cardiff, Wales, emigrated to the U.S. in 1866, at age sixteen. After studying journalism and doing public-relations work for a brewery, he headed west and covered the mining beat for a San Francisco newspaper. He earned a reputation as an expert on the industry and soon jumped into the risky, boom-and-bust business of promoting mines and selling stock. “Sometimes I made,” he told an interviewer, “and sometimes I lost.” A well-timed investment in a Mexican silver mine made him enough to buy a sprawling ranch near Los Angeles—much of it destined to become Griffith Park—and he moved there in 1882.

His marriage five years later was the real source of his wealth. Tina’s brother, Joseph Mesmer, later dismissed him as “a pretend millionaire” who saw his sister as nothing more than “a valuable prize.” Griffith even broke off the engagement at one point, accusing the Mesmer family of meddling in their affairs and trying to withhold some of her assets. The dispute was resolved, and shortly before the wedding title to all of Tina’s property was transferred to Griffith, adhering to the then-common practice of a bride bringing a dowry into the marriage. He reputedly sold off the downtown land she had inherited for close to a million dollars—thirty million in today’s terms.

He was an “expert tax dodger,” the Los Angeles Evening Express reported, and became notorious for misleading assessors who tried to confirm the value and extent of his property holdings. And his hard-nosed business practices turned a former tenant into a bitter enemy. He squared off against Frank Burkett, a recent British immigrant, in a legal battle over back rent. In 1891, after losing in court, Burkett ambushed Griffith as he sat in a buggy and shot him in the face with a blast of bird shot. Griffith, who was only slightly injured, ran for cover, and Burkett shot himself. An investigation concluded Burkett had intended to murder Griffith, but had mistakenly loaded his gun with the less lethal bird shot.

Griffith joined a Los Angeles businessmen’s club, the Jonathan, but never fit in. He was vain and boastful, drank too much, and droned on about how rich and important and generous he was. He used the title “Colonel” even though there were doubts he had ever served in the military. And he claimed he was a marked man. “My life is in jeopardy all the time,” he confided to one acquaintance. “The Catholics,” he declared to another, “are after me.” He was so convinced Catholic assassins were trying to kill him that he sometimes accused bartenders and waitresses of poisoning his drinks. The men who knew him laughed off his conspiracy theories. He was, as one Jonathan Club member put it, “a little nutty.”

Both sides lawyered up for the February 1904 trial. The Mesmer family retained Henry Gage, a former California governor, to lead the prosecution. Griffith hired some of the most expensive lawyers in the city to defend him. Tina testified with a black veil covering her face, to hide her scars and glass eye. The couple often quarreled, she revealed—over his drinking, her Catholicism, his delusions about a plot to poison him. He accused her of flirting with other men and having affairs. After enduring hours of cross-examination, she fainted and had to be carried from the courtroom.

Unable to shake her story, the defense scrambled to prove that Griffith had been legally insane when he pulled the trigger. Tina was asked to repeat the first words she said when a doctor arrived at the hotel to tend to her wounds: “Oh, the colonel is crazy, he is surely crazy!” Business associates and fellow members of his club described his heavy drinking, erratic behavior, and growing paranoia about Catholics plotting to kill him. A procession of medical experts diagnosed him as suffering from what they termed “chronic alcoholic insanity.” The prosecution countered with experts of its own who had examined Griffith and were convinced he was sane.

The jurors—all men—deliberated for six hours before returning with a compromise verdict. They rejected the insanity plea and found Griffith guilty of the less-serious offence of assault with a deadly weapon. The Evening Post-Record, incensed by what it considered a travesty of justice, reported the news under the headline, “Farce of Rich Man’s Trial Is Over.”

* * *

The judge was as outraged as the press. “A more aggravated assault I have never heard of in my experience of fourteen years on the bench,” he growled as he sentenced Griffith to the maximum penalty—two years in prison and a $5,000 fine. He spent almost a year in the county jail as his lawyers mounted a doomed appeal, then was shipped to San Quentin State Prison, north of San Francisco. The jail time did not count toward his sentence and he served another twenty months before he was released on parole in December 1906.

Tina Griffith was granted a divorce on the grounds of cruelty and given sole custody of the couple’s fifteen-year-old son, Vandell. She received a lump-sum settlement equivalent to about two million dollars today. She never remarried and lived in Los Angeles until her death in 1948.

Griffith emerged from San Quentin richer than ever, thanks to his sister’s prudent administration of his business interests while he was behind bars. He published a book condemning the horrific conditions in America’s prisons and pledged, belatedly, to support the cause of temperance. He died in 1919 at age sixty-nine.

Griffith Park’s website bills it as “the largest urban-wilderness municipal park in the United States.” It boasts hiking and biking trails, sports fields, three golf courses, and the Los Angeles Zoo. The giant letters of the famous Hollywood sign cling to one of its hillsides. Griffith’s will set aside money to build an observatory, completed in 1935, and a Greek-themed amphitheater. Fittingly, there is a park-wide ban on alcohol.

“I consider it my obligation to make Los Angeles a happier, cleaner, and finer city,” Griffith said when he donated the land. Today, a fourteen-foot bronze statue of the benefactor greets visitors at the park’s entrance. A plaque on the base acknowledges his gift but makes no mention of the day he almost murdered his wife.

———

Esquire magazine selected Dean Jobb’s book Empire of Deception: The Incredible Story of a Master Swindler Who Seduced a City and Captivated the Nation (Algonquin Books), the story of 1920s Chicago con artist Leo Koretz, as one of the 50 best biographies of all time. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. Find him at http://www.deanjobb.com/.

Copyright © 2023 Dean Jobb