Stranger Than Fiction

March 2023

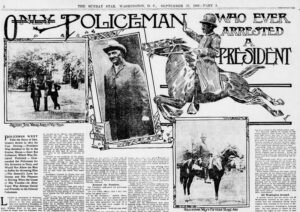

The Case of the Speedy President: A Washington Police Officer Made History When he Arrested Ulysses S. Grant in 1872

by Dean Jobb

Hooves thundered as a carriage careened along Washington’s Thirteenth Street at high speed, sideswiping a woman and her six-year-old child. Rookie patrolman William West, who was stationed at the intersection of M Street, rushed to the scene and found them lying on the pavement with serious injuries. The carriage had not stopped; by the time the officer arrived, the driver and his team had disappeared.

A crowd gathered as the victims were cared for. Residents of the neighborhood, a fifteen-minute walk from the White House—“the aristocratic section” of the nation’s capital in 1872, West later noted—had been demanding a police crackdown on reckless drivers. Carriages barreled through on their way to and from Brightwood Trotting Park as drivers sped along the dead-straight, three-mile stretch of Thirteenth Street between the racetrack and the city. Even though West had been sent to the neighborhood to deter speeders, angry onlookers seemed ready to turn on him. They were “very much excited,” West recalled, and “loud in their exclamations against the racing persons and the police.”

More carriages approached at high speed. West held up his hand to signal them to stop. Only one did.

“Well, officer,” the driver called out once he had reined in his horses, “what do you want with me?”

West recognized the stern-faced, bearded man. Everyone did. He was Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War general who saved the Union, now the eighteenth president of the United States. Surprisingly, just seven years after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, he was traveling without security guards.

The patrolman was not about to back down, not even for the most powerful man in the country.

“Mr. President,” he announced, “you are violating the law by speeding along this street. Your fast driving, sir, has set the example for a lot of other gentlemen. It is endangering the lives of the people who have to cross the street in this locality. Only this evening a lady was knocked down by one of the racing teams.”

“I am very sorry,” the president replied, “and I’ll promise that hereafter I will hold my team down to the regulation speed.” He inquired about the victims’ injuries and, as he drove away, once again assured West he would obey traffic laws.

The following evening, West was back at his Thirteenth Street post when more than twenty carriages sped toward him. The president was at the head of the pack. West again held up his hand to command the drivers to stop. Grant pulled madly on the reins but was travelling so fast that he was a block away when he finally brought his horses to a halt. A half-dozen other drivers—described as “prominent officials” and friends of the president—stopped as well and followed Grant’s carriage as he backtracked to where the officer was waiting.

It had been barely twenty-four hours since Grant had been warned to slow down. William West was about to make history as the only policeman to arrest a sitting U.S. president and charge the nation’s commander-in-chief with breaking the law.

Born in Maryland in the early 1840s, West worked as a waiter before enlisting in the Thirtieth U.S. Colored Infantry, which saw action in Virginia and North Carolina in the last year of the war. After the unit was disbanded at the end of 1865, the Treasury Department hired him as a messenger. He joined the Washington police in July 1871, reputedly one of only two African American officers serving in the department at the time.

He had been a patrolman for barely a year when he encountered the speedy president. In an era when police corruption was rampant—and money or well-connected friends could make allegations of wrongdoing disappear—West’s superior officer had urged him to do his duty, “no matter who the lawbreaker might be.”

Lieutenant Adolphus Eckloff, West recalled, “impressed on me the necessity of doing my whole duty.” Washington powerbrokers, it appears, could not count on patrolmen to look the other way. Willard Saulsbury, a U.S. Senator from Delaware, was charged with fast driving only months before the president was caught dashing along Thirteenth Street.

Grant drew up to West in his carriage. He was smiling, but it was a nervous, chastened smile. He looked, West recalled, like “a schoolboy who had been caught in a guilty act by a teacher.”

“Do you think, Officer, that I was violating the speed laws?”

“I cautioned you yesterday, Mr. President, about fast driving, and you said, sir, that it would not occur again.”

“Did I? Well, I suppose I forgot it, and that I might have been going a little bit too fast this evening.” He made a weak attempt to shift some of the blame to his horses. “These animals of mine are thoroughbreds, and there is no holding them.”

“I am very sorry, Mr. President, to have to do it,” West said, “for you are the chief of the nation, and I am nothing but a policeman, but duty is duty, sir, and I will have to place you under arrest.”

There was no posted speed limit on Washington’s streets, only signs that prohibited “fast driving.” It was an offense to drive a horse “at a pace faster than a moderate trot or gallop” or to race another rider or carriage driver. In another prosecution for fast driving that year, the arresting officer suggested a pace of ten to twelve miles per hour was “an immoderate rate of speed.”

West had to make a judgment call, and it was clear the president was driving too fast and had been racing the other carriages. It’s unlikely he knew that the Washington police had twice arrested and fined Grant in 1866, three years before he became president, for driving too fast.

“All right,” said Grant, “where do you wish me to go with you?”

The president invited West to climb aboard his carriage and they headed for the nearest police station. They chatted on the way, with Grant asking about his family and his war record. They may have discovered that West’s unit was under Grant’s command during the siege of Petersburg, Virginia in the summer of 1864. West no doubt considered the man sitting beside him to be a hero. Grant’s administration protected and extended the civil rights of African Americans in the chaotic years after the Civil War, including passage in 1870 of the Fifteenth Amendment that protected the right to vote regardless of race or color.

West “would not get into any trouble for making the arrest,” Grant assured him, “as he admired a man who did his duty.”

At the police station, Grant was required to post a bond of twenty dollars—equivalent to about $460 today—and ordered to appear before Judge William B. Snell in police court to enter a plea and to stand trial if he chose to fight the charge. The president was not in the courtroom when his name was called the following morning, so his bond was forfeited. Twenty dollars was the usual fine for a fast-driving offense if he had pleaded guilty or been convicted.

The half-dozen drivers who stopped along with Grant were also charged. They stood trial amidst the daily parade of drunks, rowdies, and petty thieves who passed through the police court. Almost three dozen “ladies of the most refined character and surroundings”—presumably residents of the beleaguered Thirteenth Street neighborhood—joined West in testifying against the speeders. Snell, a former Maine state senator who was lauded in the press as an “honorable and upright” judge, convicted them all and “delivered a scathing rebuke” to the reckless drivers.

West was a member of the Washington police force for thirty years and was a mounted patrolman for much of his career. His claim to fame as the officer who arrested a president was mentioned now and then when his name was in the news. He was dispatched to Maryland in 1879 to investigate a series of burglaries that had stymied the local police, and he won praise for catching the culprit. He was said to have trained his horse to seize a suspect’s coat collar in his teeth as he made arrests. And he was one of two mounted officers given the honor of escorting William McKinley’s carriage as the president-elect was conveyed to the Capitol for his inauguration in 1897.

West’s name, however, was often in the papers for the wrong reasons. He faced disciplinary action for neglect of duty in 1884 after arguing about “political matters” with a fellow officer on the street for half an hour; both used language that passersby considered “warm and improper.” After he reneged on a forty-six-dollar loan in 1898 his superiors ordered him to repay the money or face dismissal from the force. A conviction and ten-dollar fine for “disorderly conduct” in 1901 led to more disciplinary action for behavior unbecoming an officer, and he was allowed to retire. The Colored American, a Washington newspaper that promoted equality for Blacks, rushed to his defence, claiming he had been railroaded on a “trivial” matter and “subjected to unnecessary humiliation and annoyance.”

Grant and West apparently met and chatted several times after the arrest. “Their love of horses,” noted one account, “was the great bond of sympathy.” And they both liked to ride fast. Not long after his retirement, West spent a night in jail after being arrested for speeding on Pennsylvania Avenue in a buggy.

West did not speak publicly about Grant’s arrest until 1908, when his first-hand account of the encounter appeared as a Sunday feature in the Washington Evening Star (it’s the source of the stilted and no doubt embellished conversations between the officer and the president reproduced in this article). He died in 1915.

Grant was re-elected in 1872, the year of his arrest, and lost a bid for the Republican nomination—and a possible third term—in 1880. He died of throat cancer in 1885. The story of his arrest was largely forgotten until 2018, when then-president Donald Trump’s legal woes raised the question of whether a sitting president could be prosecuted for alleged offenses committed while in office. “Can the president of the United States actually be indicted?” asked an item published in the Washington Post that recounted Grant’s arrest. “The prevailing answer is this: Nobody is sure.”

An arrest 150 years ago for the minor offense of speeding, however, is unlikely to be of much value as a legal precedent if a sitting president is accused of serious crimes. Grant allowed himself to be arrested, cooperated with West, and commended the officer for doing his duty. The crucial legal issue of whether West had the power to detain and charge a president in the first place was never debated or resolved.

———

Dean Jobb’s latest book, The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer (Algonquin Books), won the inaugural CrimeCon Clue Award for True Crime Book of the Year and was longlisted for the American Library Association’s 2022 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence. He teaches in the MFA in Creative Nonfiction program at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Find him at www.deanjobb.com