Stranger Than Fiction

November 2022

“I’ve Got a Bridge to Sell You”: The Con Artist Who Peddled the Brooklyn Bridge

By Dean Jobb

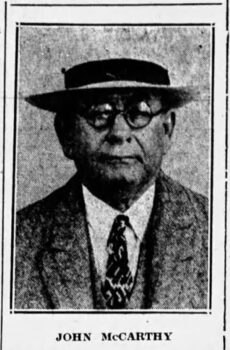

The prisoner hauled before a Brooklyn judge in 1928 did not look the part of one of the most notorious criminals in history. He squinted at the world through round-framed spectacles. When he removed his broad-brimmed hat, the sudden exposure of the baldness beneath added years to his appearance.

“A pudgy little man, with only a vague collar of chestnut hair,” was the assessment of James Kilgalen of the International News Service, one of the journalists in the courtroom that day. “He seemed old and tired.” Other newsmen were more charitable in their descriptions. One called him “a meek lamb.” Another thought he could pass for a retired stockbroker. Yet another found him “still alert of mind and fast in repartee.”

“He’s one of the smartest men I’ve ever met,” noted one of the detectives who had hunted him down and arrested him for passing a worthless check. “Might have been a judge, or a doctor,” and he could have “gone far” if he had not been “too lazy to use his mind in the right direction.”

The man was sixty-eight, born the year before the outbreak of the Civil War. He had been arrested more than a dozen times and had spent years in New York’s infamous Sing Sing prison.

His name? That depends. Some knew him as William McCloundy, others as Mr. Roberts or Mr. Taylor. When he was posing as the captain of an ocean liner, he went by George C. Parker. He had brazenly signed the name “I.O.U. O’Brien” on checks and gotten away with the ruse. Police officers who remembered the day he walked out of a prison where he was serving time, posing as the man in charge, nicknamed him “The Warden.” Lately he had been calling himself Albert Murch.

The New York police considered him “an aristocrat of crookdom.” In the press, he was crowned the “dean of confidence men” and “the biggest of the big-time” swindlers. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle hailed his signature fraud as “the epic of the confidence world.”

His real name appears to have been John McCarthy. And he was the con man who sold the Brooklyn Bridge.

It was hailed as the Eighth Wonder of the World. The Brooklyn Bridge was “the greatest work wrought by the hand of man” in the nineteenth century, Brooklyn’s Daily Eagle proclaimed on the day it officially opened in May 1883, a “monument to human ingenuity, mechanical genius and engineering skill.” It was then the longest suspension bridge in the world, spanning the East River to connect Manhattan Island to Brooklyn. The span and roadway approaches stretched for more than a mile. The soaring, Gothic-arched stone towers were, for a time, the tallest structures in the Western Hemisphere. It took more than a dozen years to build, at a cost of sixteen million dollars—the equivalent of about $425 million today. It was simply, the New York Tribune asserted, “the greatest Bridge the world ever saw.” The vaudeville comedians who delighted in bashing the borough at the eastern end of the bridge, however, remained unconvinced. “All that trouble,” one wisecracked, “just to get to Brooklyn.”

The bridge was also a magnet for crime. Allegations of fraud, graft, and political corruption dogged the massive project during the construction phase. Once it opened, thousands of people crossed on foot every day and crammed the walkways for weekend strolls, offering tempting targets for pickpockets. “The bridge is likely to be a favorite field for the operations of . . . the light fingered fraternity,” noted one press report. The warning came too late for James Cruikshank, a Long Island man who inspected the bridge soon after it opened and was relieved of his gold watch. The bridge had its own police force and, in 1885 alone, officers made 228 arrests for offenses ranging from drunkenness and assault to theft and swindling. Even one of the boys hawking newspapers to passersby near the bridge tried to get a piece of the action. One tearfully told a potential customer he needed to sell his stack of papers or his parents would beat him when he got home, then absent-mindedly switched sob stories and claimed he was an orphan.

The bridge itself was a money-making machine. For many years tolls were collected from everyone who crossed—ten cents for a horse-drawn wagon, three cents for pedestrians and cyclists—and the pennies added up. Annual revenues topped a half-million dollars by the end of 1884. Despite the bridge’s grandeur and financial prospects, the editor of a Milwaukee paper was unimpressed and offered some pointed advice to his readers. “If anybody comes around here selling stock in that bridge,” he warned, “don’t any of you invest a dollar.”

Sometime in 1885, with the bridge a commercial success, McCloundy/ Parker/O’Brien/McCarthy/Murch—let’s call him McCarthy—hit upon the idea of selling New York’s newest landmark, or a stake in it, at least. The twenty-five-year-old swindler, in the words of journalist James Kilgalen, was suave, “a ‘slick’ talker, and a dapper dresser” who found it easy “to strike up acquaintance with gullible strangers.” McCarthy prided himself on ignoring rubes and preying on bigger fish. He seemed to relish the challenge of duping well-heeled victims who should have known better. It was “the clever ones that fall,” he once told New York detective Charles Kane.

McCarthy was “a smooth, high-pressure salesman invariably giving his customers a good ‘bargain,’” Kane recalled. To sell his bridge-investment scheme, the detective explained, he touted “the very fine return” to be made from toll revenues “in view of the large amount of traffic involved.”

His first target was a visitor from Indiana, who was hooked by the sales pitch and agreed to McCarthy’s terms: $1,000 cash and $4,000 more to be paid in quarterly installments. The day he handed over the initial $1,000, of course, was the last time he saw McCarthy.

How many times McCarthy pulled the swindle is unknown. Kilgalen, writing in 1928, claimed he sold the bridge “over and over” and the Brooklyn Times Union reported that his bridge frauds alone netted $50,000. And it’s not clear that he first sold the bridge in 1885—the scam does not appear to have attracted press coverage at the time, and some later accounts claim he pioneered the fraud in 1895 or 1901. If the latter date is correct, he may have stolen the idea from Edward Brasso, who was reportedly doing a brisk business of selling the bridge to Italian newcomers as early as 1900.

McCarthy soon moved on to a new but similar scam, selling lots in New York’s City Hall Park to unwary New Englanders for $25,000. His first conviction for grand larceny, in 1901, earned him two and a half years in Sing Sing. Soon after his release he was convicted of forgery and imprisoned for four more years. He was sent back to Sing Sing in 1911 for theft and passing a worthless check. Convictions for forgery in 1917 and theft in 1923 put him once again behind bars. After being caught trying to loosen a stone in the wall of his cell, he devised an easier way to escape: He got his hands on the warden’s hat and coat, confidently exchanged greetings with guards as he passed, and walked out of the prison. He was soon recaptured and the caper added six months to his sentence.

New York police estimated McCarthy reaped as much as a million dollars during his swindling career. His victims, they believed, included prominent people who refused to report their losses, fearing they would be subjected to public ridicule. And it was easier to separate fools from their money “in the good old days,” he lamented as detectives questioned him about his criminal record, “before the police became so systematic.”

He seemed unable to pass up a chance to make a quick buck at someone else’s expense. As he awaited his court appearance in 1928, one of his suspected victims was brought to the police station to see if he could identify McCarthy. The man, who had been swindled out of $10,000, did not recognize him and, as he left, the incorrigible and ever-optimistic con man sensed an opportunity.

“Let me have your card,” he said. “We may be able to do business some time.”

McCarthy’s final scam was modest. The bogus check he tried to cash in 1928 was for a measly $150. But when the police picked him up in New Jersey for that offense, he was on the verge of a big payday. He was about to sell ten building lots in Asbury Park to a realtor for $17,000. McCarthy, of course, did not own the lots.

His timing could not have been worse. Under a state law introduced in 1926, repeat offenders convicted of a fourth felony received an automatic sentence of life in prison. McCarthy’s criminal record put him well over the threshold and he was dispatched to his alma mater, Sing Sing, in November 1928. “It looks like a sad Christmas,” noted one news report. “for the last of the old time crooks.” He died in prison eight years later.

The Detroit Free Press thought there was a lesson in McCarthy’s audacious fraud. “Crooks are sent into the world to teach those who want to get rich quick that there is no royal road to riches,” the paper editorialized. “They will go on selling Brooklyn bridges as long as people can be induced to buy them, which looks as if it might be until the end of time.”

McCarthy’s swindle has become the ultimate con, synonymous with gullibility and blind trust. The catch phrase, “if you believe that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you” has been around almost as long as the bridge has been standing.

When New Yorkers celebrated the bridge’s one hundredth birthday in 1983 with parades and fireworks, the structure went on sale for real. Bits of wooden walkway and slivers of cable salvaged during repair work were sold as souvenirs, and ten dollars bought a certificate purporting to be the deed to the bridge, signed by Sid E. Slicker.

On the eve of the celebrations, New York cab driver Lou Henderson told a journalist the iconic bridge ranked with the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building as a landmark tourists wanted to see.

“Brooklyn Bridge is still the most, the greatest,” he said. “One of these days I’m gonna get lucky and find a buyer.”